Finding the mix that clicks!

Gepubliceerd op 09 01 2024A STUDY ON THE ROLE OF THE CHANNEL MIX IN SHAPING ADVERTISING IMPACT

Mark Vroegrijk

Senior Specialist Data, Science & Analytics

In today’s advertising landscape, “cross-media” campaigns, in which a brand simultaneously advertises on multiple channels, have become the rule rather than the exception. In a previous study, we have shown that consumer awareness of a campaign not only depends on the overall level of media pressure behind it but also on the number of channels between which this media pressure is divided.

We discovered that the ideal number of channels increases with campaign size; however, even for large-scale campaigns no more than four channels are recommended to maximise campaign awareness. For campaign managers, this confirms the importance of carefully selecting the channels they will (and will not) be advertising on. To provide more insight that can help drive such choices, we now extend our previous study in order to explore what role the types (rather than amounts) of channels in the media mix play in driving marketing campaign effectiveness.

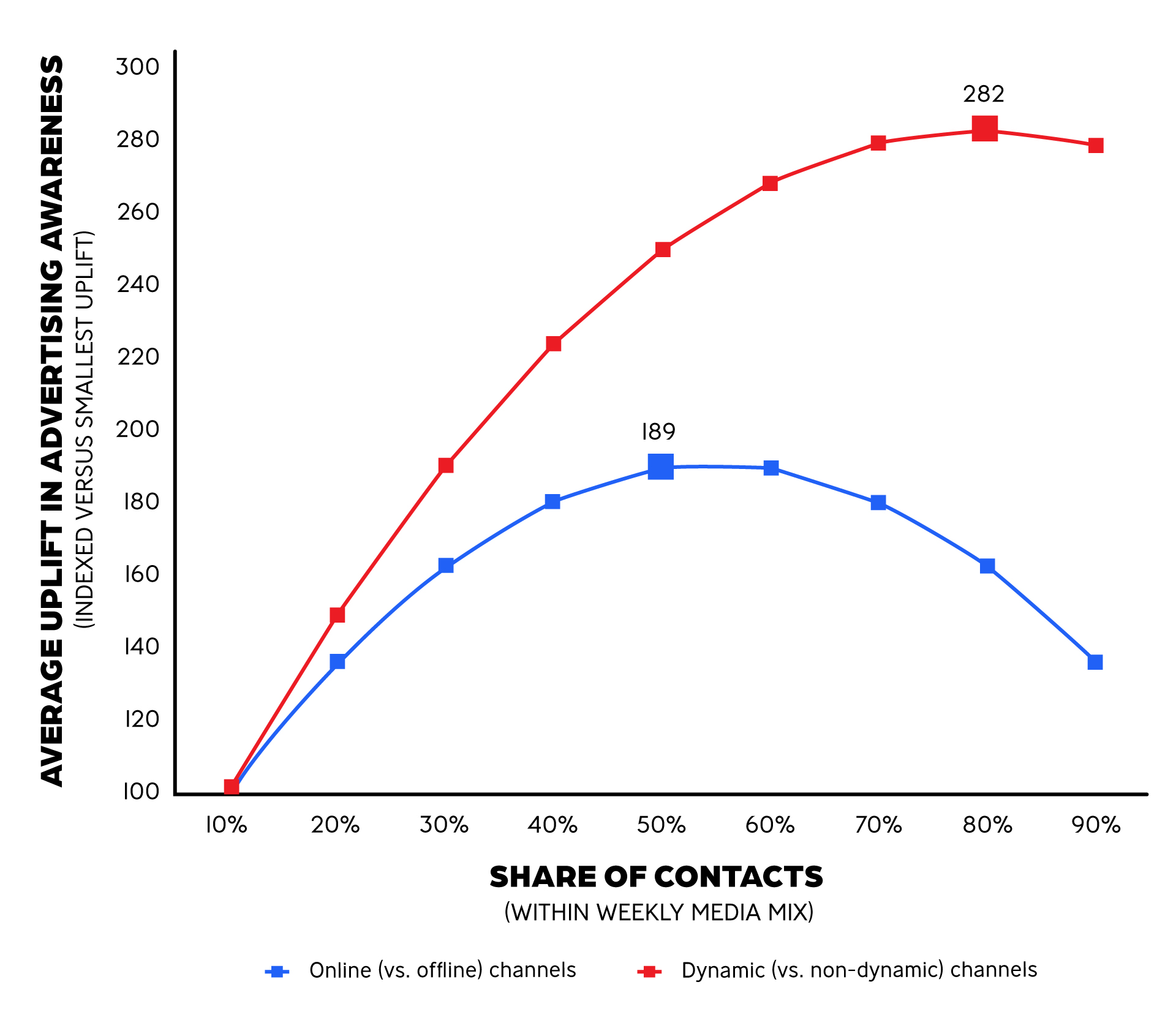

We show that the impact of a certain amount of media contacts depends on how many of these contacts were realised online (versus offline) and on “dynamic” (versus “non-dynamic”) channels – the latter typology reflecting whether video- or audio-based advertising is commonly seen on the medium. We do so through a (regression) analysis of media pressure on advertising awareness, using a data set covering 34 brands across 8 categories. Figure 1 shows how the relative prevalence of these channel types can affect campaign awareness returns.

Figure 1: Average (indexed) uplifts in advertising awareness under different shares of media contacts on online (versus offline) and dynamic (versus non-dynamic) channels

When it comes to online versus offline channels, our findings reveal that a more-or-less equal (50/50) distribution of campaign impressions across these two types of channels leads to the strongest uplifts in advertising awareness. Such increases are nearly twice as strong compared to distributing the same number of media contacts (almost) entirely offline (90/10).

An even more pronounced (tripled!) effect is found when setting the share of “dynamic-channel” contacts within the media mix to the optimal level. This strongest impact is in fact seen when the vast majority (80%) of campaign impressions is realised on such channels. In conclusion, as long as media budgets allow it, the most effective channel mix for raising campaign awareness puts equal focus on online and offline media, but strongly prioritises dynamic channels (e.g., TV, radio, pre-rolls and social) within each of these formats.

EXTENDING THE MEDIA-PRESSURE – CAMPAIGN-AWARENESS MODEL

In this study, we build upon our previous research that explored how the success of advertising campaigns is influenced by the number of different channels used. To do so, we use the same dataset as before, which contains weekly data on the number of media contacts brands made through 8 different channels as well as their advertising awareness scores – primarily collected from tracking studies in the Dutch market. The data cover 34 brands; mainly in the electronics, FMCG and insurance industries, each with an average of about 2 years worth of data (106 weeks).

To understand how the distribution of media pressure across different channels (referred to as the channel mix) impacts its effectiveness, we will start with the same regression model we used in our previous analysis. However, instead of using our internally developed RPS metric to measure weekly media pressure, we will use a simplified version. This simplified version still accounts for consumers (partly) remembering media contacts from prior weeks, but it removes the channel-specific weighting. Typically, this weighting controls for differences in the memorisation potential of various channels within the media mix. Since our study’s main focus is on the composition of the media mix itself (and its impact), we want to explicitly model its effects rather than include them implicitly.

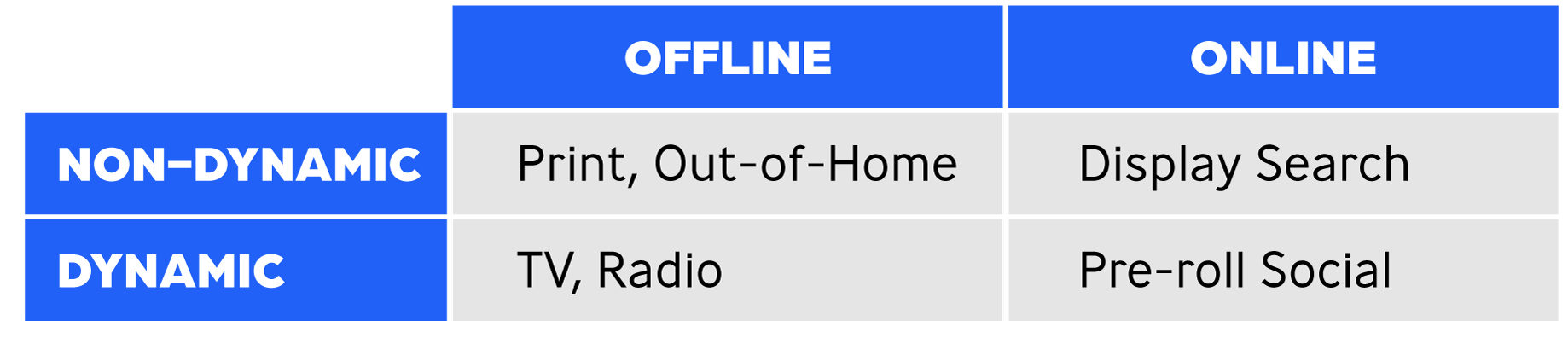

To do so, we first need to decide how to operationalise the media mix within the model. We choose to classify each of the eight channels covered by our data set along two (dichotomous) typologies:

- online versus offline:

Online channels are accessed through the internet (search engines, social platforms or other websites) in order to have their advertising content consumed, while offline channels present advertising through (for example) in-home cable connections (TV) or at outdoor public spaces.

Online channels are frequently perceived as being able to reach different consumer segments than offline channels (e.g., younger consumers) and to target more precisely via cookies or user profile information. Offline channels, on the other hand, are less “cluttered,” with fewer ads competing for the consumer’s attention at the same time.

- dynamic versus non-dynamic:

Dynamic channels mainly contain ads of a fixed duration during which different “moving” elements of a visual and/or aural nature are presented, while non-dynamic channels mainly contain ads that present their message in a more “static” fashion.

Compared to non-dynamic channels, dynamic channels make it possible to convey more elaborate messages, sometimes even in a “story-like” matter. At the same time, the fact that the visual and aural elements used in ads on these channels “come and go” implies that consumers cannot focus on specific parts of the message for as long as they like or need – which may hamper understanding.

Combining these two typologies provides us with four possible combinations of media channels, as shown in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Two-dimensional classification of media channels

For this research, we expanded our previous model by adding two new variables: the proportions of weekly contacts made through online and dynamic channels, respectively. These variables, incorporated as moderators of the relationship between media pressure and advertising awareness, help us understand how online (vs. offline) and dynamic (vs. non-dynamic) channels influence the effectiveness of the media mix. We also allow for different effect patterns by using both linear and squared terms for these variables. See Figure 2 for a visual representation of the model adjustments (indicated by the white-coloured circles, representing the two extra moderators).

Figure 2: Extended conceptual model for the role of the channel mix in determining advertising effectiveness

* This is a simplified variant of DVJ Insights’ RPS metric for weekly media pressure, which still accounts for consumer memorisation, but leaves out channel-specific (impact-based) weighting of contacts.

equal split equals success?

After estimating the extended regression model as described earlier, we can use its parameters to predict uplifts in advertising awareness based on different distributions of media pressure across online and offline channels, as well as dynamic and non-dynamic channels.

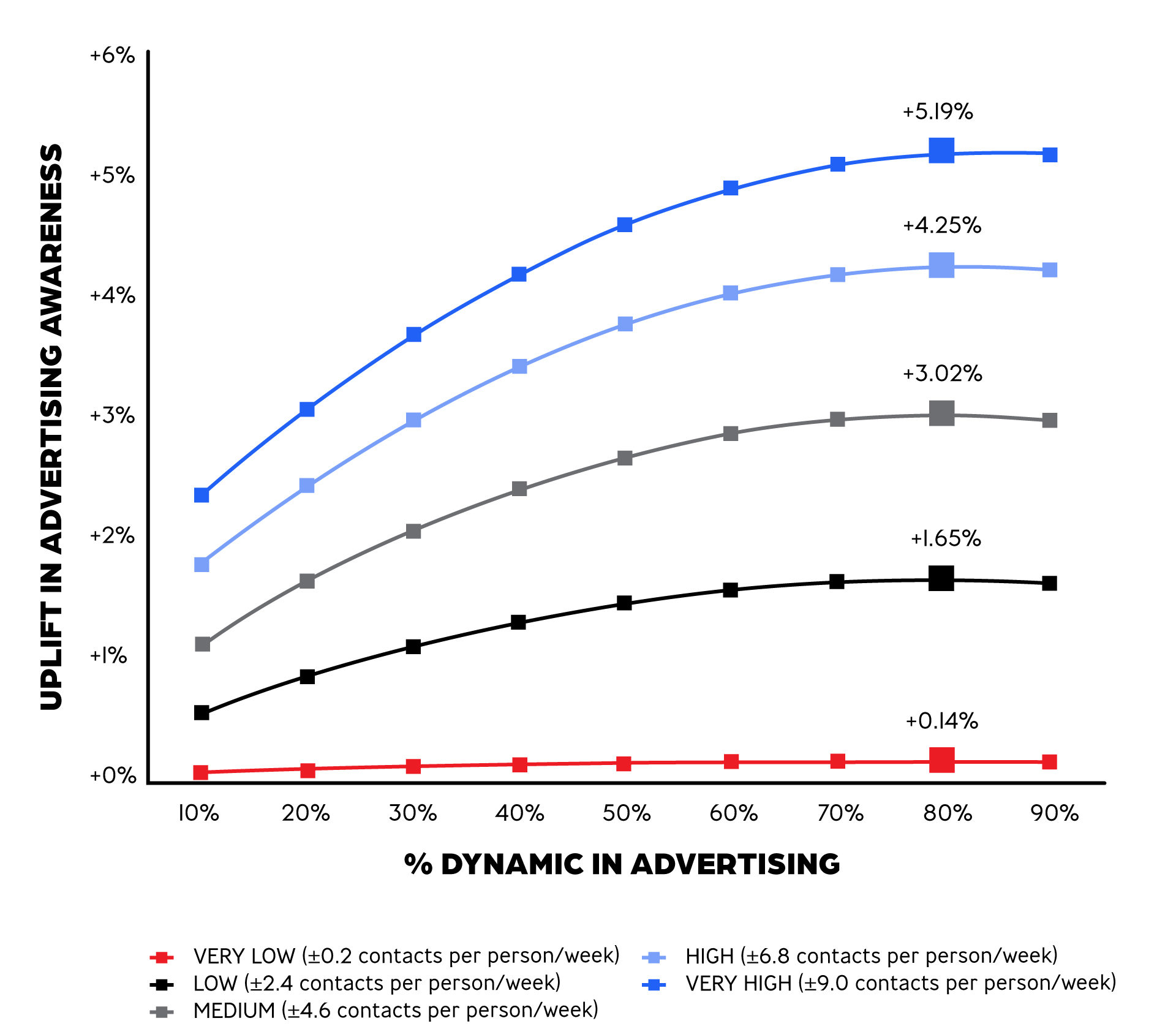

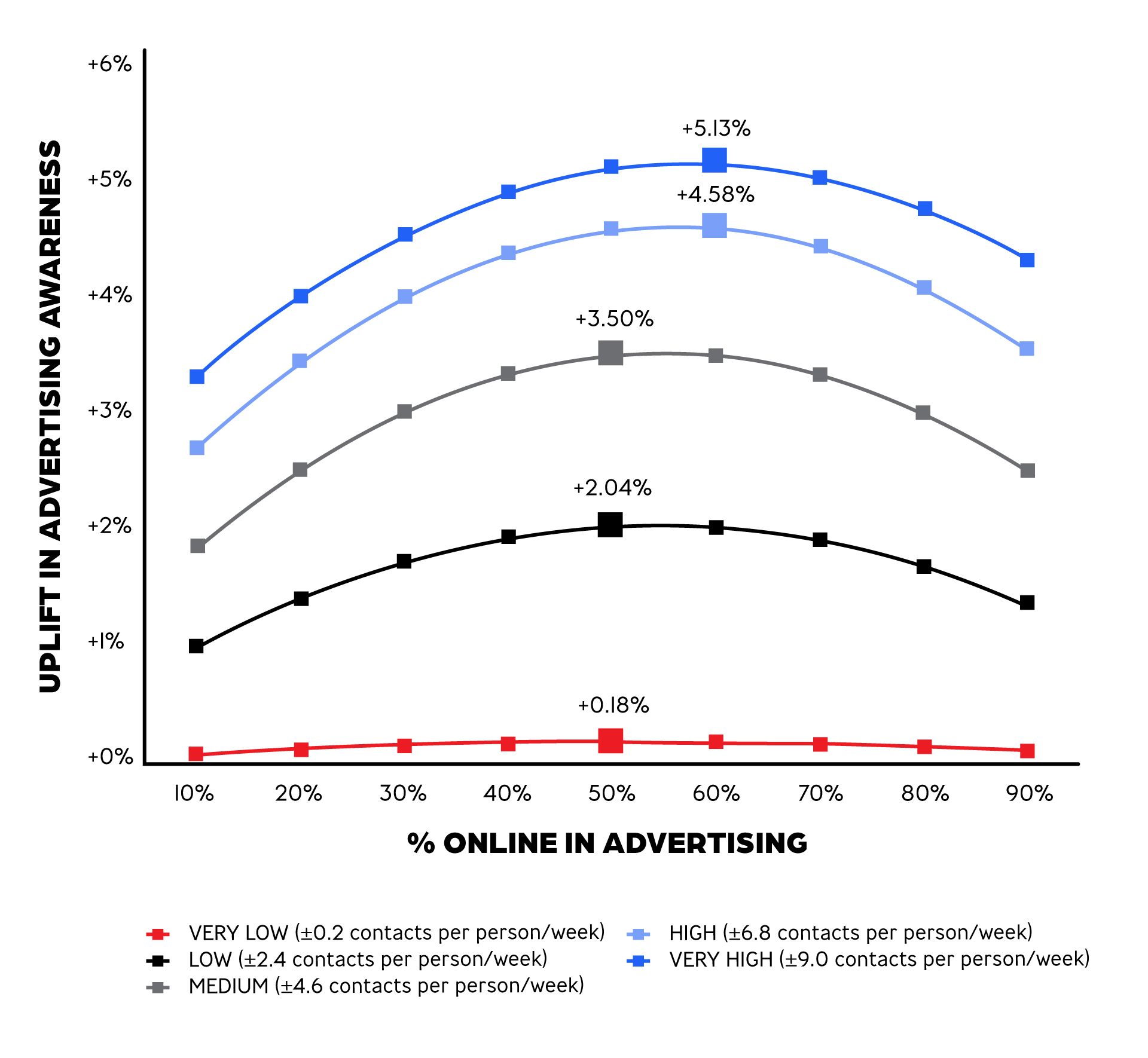

We compute these predictions for various levels of weekly media pressure, ranging from very low (at the bottom 10 level in our data set) to very high (at the top 10 level in our data set). Figure 3 below displays the results of these predictions, with panels A and B covering the effects of different shares of contacts on A) online vs. offline and B) dynamic vs. non-dynamic channels, respectively.

Figure 3: Expected uplifts in advertising awareness under different levels of media pressure and shares of media pressure realised on online (panel A) and dynamic (panel B) channels

Both of these graphs show that the higher the overall level of media pressure is, the more a clear “optimum” reveals itself when it comes to the share of contacts on different types of channels.

If we first zoom in on panel A, we find that the largest uplifts in advertising awareness are generally found when the media pressure behind a campaign is more or less balanced between online and offline channels. For smaller to medium-sized campaigns, the optimum actually lies at an exact 50/50 split between online and offline contacts. Both types of channels may serve to reach different consumers, but both of them also need to be sufficiently supported in order to do so effectively.

For larger campaigns (with a greater number of media contacts available), we see the best results with a 60/40 online/offline split. Because both types of channels now surely have enough pressure behind them to (sufficiently) reach their associated part of the audience, it may be wise to (slightly) start prioritising online contacts – as the impact of this type of contact, in particular, can be further enhanced through smart user targeting.

Optimal Distribution: Dynamic VS. Non-Dynamic Channels

When it comes to the most effective distribution of contacts across dynamic versus non-dynamic channels, panel B reveals a very clear pattern. Across all levels of media pressure, the optimum share of dynamic-channel contacts stays the same – at a very high level of 80%. This is maybe not too surprising because advertising on dynamic channels can use various “moving” elements (both visual and verbal), offering better opportunities (compared to static ads) to convey a key message and/or to provide a large number of “memory hooks” that help consumers remember the campaign.

At the same time, contacts using a dynamic channel are typically more expensive than contacts using a non-dynamic channel, so the true optimum share of dynamic-channel contacts may be “as much as the campaign budget allows.” At the same time, the 80/20 optimum shows that brands do benefit from realising at least some of their media pressure on non-dynamic channels, demonstrating that these channels can still add value to a media mix. For example, out-of-home ads can help the brand to be present at places where dynamic channels may be less accessible, while online search advertising can reach consumers during a high-involvement stage in their customer journey.

EACH CHANNEL HAS ITS PLACE

Our study on the role of online and dynamic channels within marketing campaigns has revealed that both types of channels can enhance the effectiveness of the media mix. At the same time, they should not solely be relied upon – as the optimum shares for these channels always lie below 100%. This shows that both offline and non-dynamic channels can also add value to a media mix – and that a cross-media approach, in which one advertises on different (types of) channels, is thus good practice.

Dynamic vs Non-dynamic channels

Still, more resources are ideally devoted to some types of channels than to others. For dynamic channels, which enable the use of video and audio in advertising (e.g., TV, radio, online pre-rolls and social), we find that if the campaign budget allows it, 4 out of 5 media contacts should be realised on them. Even though we decided not to incorporate the channel-specific (impact-based) weighting of contacts from our RPS measure into our analysis, this high optimum of 80% does support the greater weights we usually attach to these channels.

Online vs Offline

For online versus offline channels, we find that a more or less equal split of contacts across both types (50/50, or 60/40 for larger campaigns) works best in maximising consumer awareness of the campaign. This is in line with earlier findings on this topic, e.g., with one of the key outcomes of the Advertising Research Community project being that spending 45% of campaign budgets on online channels results in the highest ROI. Offline as well as online channels thus each still have their benefits, and we advise marketing managers not to (heavily) prioritise one over the other, but instead to capitalise on each type’s unique strengths to maximise the impact of their campaigns.