The impact of brand and message cues in online video-based advertising on viewer skipping behaviour

- DVJ Research Group

- Aug 29, 2025

- 7 min read

Blog by Bart van de Mortel

Nowadays, online video-based advertising is often provided in a setting where the viewer gets to decide whether they want to watch the ad in full, or skip it prematurely. However, just like for more traditional ways of advertising, this means that skippable video ads remain prone to ad avoidance or at least ‘full ad’ avoidance. Since viewers are actively viewing their screens for a specific purpose in online video settings (e.g., when they want to watch specific YouTube videos), they are more likely to be irritated by ad interruptions, and thus will be more likely to skip these ads (Campbell et al., 2017). If viewers indeed choose to skip ads early on, advertisers have little time to get their message across and pitch their product or service – making it vital that the brand and key takeaways are communicated clearly and as soon as possible. However, this may by itself form a “catch-22”, with several academic as well as practical marketing studies showing that brand and message cues themselves may accelerate skipping behaviour even further. Still, these findings apply mainly to TV – a channel on which ads are typically longer and more “story-like” than the bite-sized video’s that are typically used in online environments. Therefore, this research explores what impact brand and message cues have on skipping behaviour specifically for online video-based ads, and whether specific types of cues work better in this regard than others. This provides new insights to creators of future online video-based ads, which can be used to optimise the effectiveness of such ads.

Data

The datasets used for the study contain data on consumer skipping behaviour for TikTok (in-reel) and YouTube (pre-roll) ads, obtained through two different survey-based experiments. In each experiment, participants were asked to scroll through several online environments at their own pace. For the experiment on YouTube pre-roll ads (conducted among respondents in 7 different countries), two of the online environments were mockups of sites with video content, preceded by an ad. To get to the actual content faster, participants could skip the ads after 5 seconds had passed. In the experiment on TikTok reel ads (conducted among respondents in 4 different countries), two of the environments were reels of six videos each, with one of them being an ad. All of these videos, including the ads, could be skipped by participants at any point in time. In both experiments, the two ad environments were randomly intertwined with four news/sports websites, to emulate a typical browsing session for the participant. Data was collected on the total time participants viewed each video ad, whether they could subsequently recall the brand(s) in them and whether they understood their message. In total, the datasets cover 216 YouTube pre-roll ads 128 TikTok social reel ads.

Any ad that was skipped before the participant of the experiment had viewed 6 seconds, was considered “skipped”. Conversely, any ad that was viewed for at least 6 seconds was deemed “not skipped”. This threshold of 6 seconds was chosen because pre-roll ads could only be skipped after five seconds, and the extra second was necessary to account for the time between the option of skipping appearing and the time at which a participant could feasibly press the skip button. Then, all ads in the study were coded based on whether they contain various brand and/or message cues (as discussed below) within the first 5 seconds of the ad. So, combining the skipping behaviour of viewers in response to an ad with the cues it contains, enables the possibility to investigate what impact these cues have on the probability of an online video ad being skipped.

Features

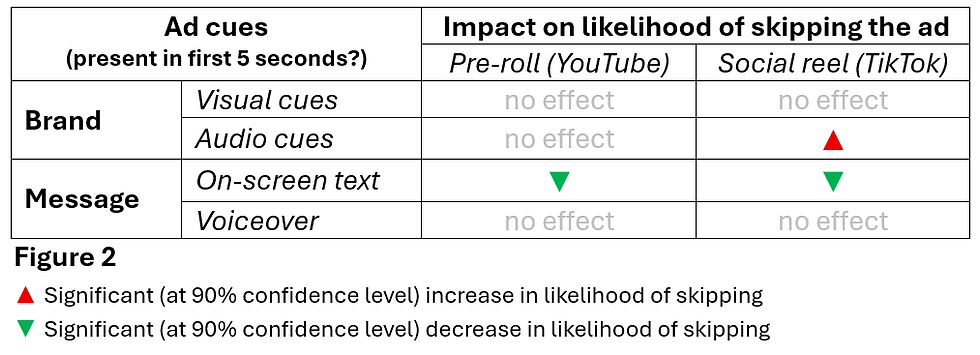

This study analyses the effects of both brand and message cues on the probability that a person skips an online video ad. Specifically, the brand cues investigated in this study are: whether the brand name appeared on screen at least once (visual cues) and whether the brand name was spoken out loud at least once (audio cues). Turning to the message cues, the study classifies ads based on whether (part of) the message is conveyed through on-screen text, and/or through a voice-over. The study then uses the ad’s platform (TikTok or YouTube) as a moderator to further look into differences between the effects of the various brand and message cues on the odds of skipping for each platform. The conceptual framework of the study is displayed in Figure 1, and the different relationships included in this framework are tested through logistic regression analysis.

Figure 1

Key findings

Starting with the effects of message cues, the study finds that displaying text on a viewer’s screen in an online video ad (in order to (partly) communicate the ad’s main message) actually decreases the likelihood of skipping. The appearance of on-screen text can draw attention, and when the viewer decides to actually read this text, they will be much less likely to press the skip button. Communication of this message through a voice-over instead has no significant impact on skipping behaviour. Even though the finding that any message cues in online video do not accelerate skipping behaviour is a positive outcome, using written text still edges out here, as it actually contributes to retaining the viewer’s attention.

Turning to the impact of brand cues, the analysis results reveal that the presence of visual cues (i.e. the brand name appearing on screen) does not significantly affect skipping behaviour. This is a striking result, given that prior studies found that for TV advertising, showing your brand may actively drive viewers away from your ad. An explanation may be that brand cues are perceived as more disruptive in advertisements that are more “story-like” – such as TV commercials – while they fit better with the shorter, “to-the-point” nature of online video advertisements. Alternatively, the online environments themselves, in which users can be exposed to a multitude of ads within a short timeframe (e.g., banner ads, homepage takeovers, in-app advertising), may make viewers more tolerant of any branding efforts they encounter.

However, the picture changes slightly when it comes to brand cues that are spoken instead of shown (audio cues). While such cues still do not significantly impact viewer retention when they appear in YouTube pre-rolls, they do lead to more skipping for TikTok reel ads. A reason for this finding may lie in sound being especially central to the user experience on the TikTok platform, with many videos including music, singing voices and/or speech. A brand name that is spoken out loud may then “stick out” and pull viewers out of the native feel of the video, leading to increased ad avoidance.

Figure 2 below summarises the main findings of the study.

Managerial implications

An important conclusion that can be taken from the results of this study is that the effect of branding cues on viewing behaviour for video-based ads may heavily differ between platforms and their associated ad formats. While the appearance of brand cues tends to lead to increased skipping of TV commercials, their impact is way less pronounced for video-based advertising on online platforms. Only audio-based cues were found to accelerate consumer skipping, and then only for TikTok (and not YouTube) ads. This means that branding proves less of a “balancing act” on online platforms. Especially, visual cues are effective ways for advertisers to convey their brand to the viewer, without the risk of alienating them.

When it comes to the (less previously-studied) message cues in an ad, the study also paints a positive picture, with neither text-based nor voiceover-based cues being associated with an increased likelihood of skipping. Advertisers on online platforms thus do not have to convey their message through abstract imaging and/or storylines, but can be pretty “upfront” about it. Still, when a choice between on-screen text and voiceovers is presented, the former wins out, as it manages to both draw attention and keep viewers occupied while reading the text. This, in the end, can even prevent viewers from skipping.

Selected references

Allan, D. (2006). Effects of popular music in advertising on attention and memory. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(4), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.2501/s0021849906060491

Becker, M., Scholdra, T. P., Berkmann, M., & Reinartz, W. J. (2022). The effect of content on zapping in TV advertising. Journal of Marketing, 87(2), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222429221105818

Belanche, D., Flavián, C., & Pérez-Rueda, A. (2017). User adaptation to interactive advertising formats: The effect of previous exposure, habit and time urgency on ad skipping behaviors. Telematics and Informatics, 34(7), 961–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.04.006

Belanche, D., Flavián, C., & Pérez-Rueda, A. (2020). Brand recall of skippable vs non-skippable ads in YouTube. Online Information Review, 44(3), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1108/oir-01-2019-0035

Campbell, C., Thompson, F. M., Grimm, P. E., & Robson, K. (2017). Understanding why consumers don’t skip Pre-Roll video ads. Journal of Advertising, 46(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1334249

Choi, Y. K., Yoon, S., Kim, K., & Kim, Y. (2019). Text versus pictures in advertising: effects of psychological distance and product type. International Journal of Advertising, 38(4), 528–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1607649

Fleck, N., Michel, G., & Zeitoun, V. (2013). Brand Personification through the Use of Spokespeople: An Exploratory Study of Ordinary Employees, CEOs, and Celebrities

Featured in Advertising. Psychology and Marketing, 31(1), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20677

Gerber, C., Terblanche-Smit, M., & Crommelin, T. (2014). Brand recognition in television advertising: The influence of brand presence and brand introduction. Acta Commercii, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v14i1.182

Joa, C. Y., Kim, K., & Ha, L. (2018). What makes people watch online In-Stream video advertisements? Journal of Interactive Advertising, 18(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1437853

Teixeira, T., Wedel, M., & Pieters, R. (2010). Moment-to-Moment Optimal Branding in TV Commercials: Preventing Avoidance by Pulsing. Marketing Science, 29(5), 783-804.

Teixeira, T., Wedel, M., & Pieters, R. (2011). Emotion-Induced engagement in internet video advertisements. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(2), 144–159. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0207

Tom, G., Clark, R., Elmer, L., Grech, E., Masetti, J., & Sandhar, H. (1992). The use of created versus celebrity spokespersons in advertisements. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 9(4), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363769210037088

Vroegrijk, M. (2023). How brand mentions in television advertising affect consumer attention, recall and evaluation. Applied Marketing Analytics, 8(4), 353–366. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/hsp/ama/2023/00000008/00000004/art00004